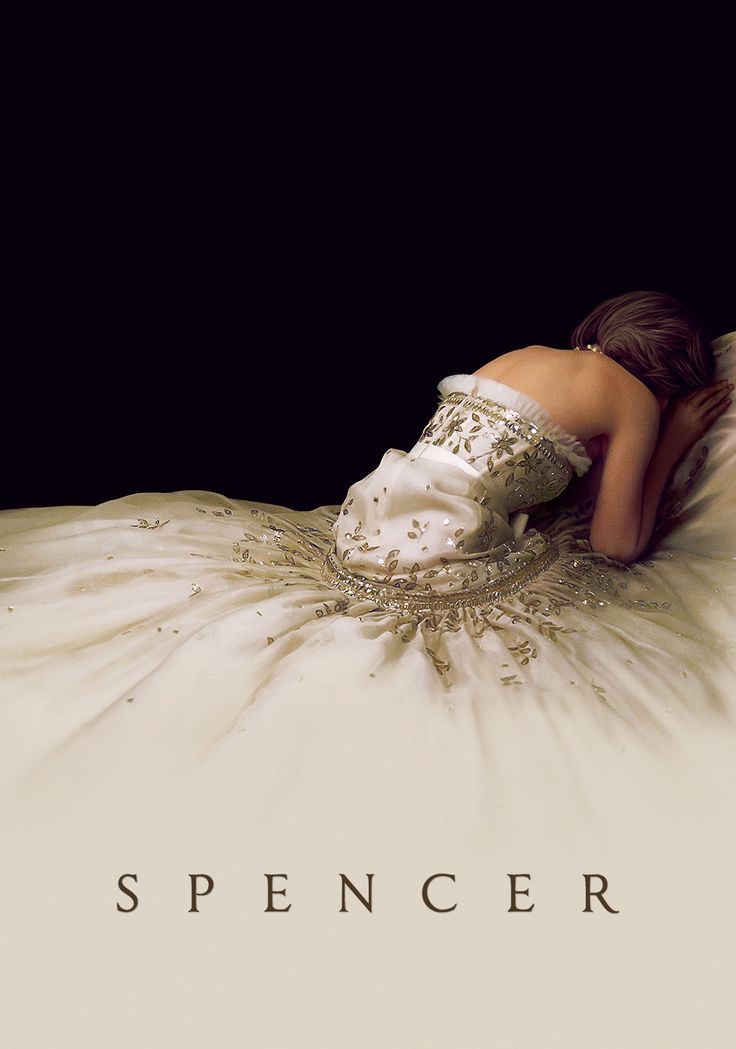

Fashion in cinema is not just an outer garment – it is a silent yet powerful language. Through every stitch and seam, characters become more vivid, their pasts are hinted at, their personalities are etched, and even their inner conflicts are woven into each layer of fabric. On the grand silver screen, costumes become witnesses to the entire storytelling journey – both subtle and irreplaceable.

When a dress becomes the narration

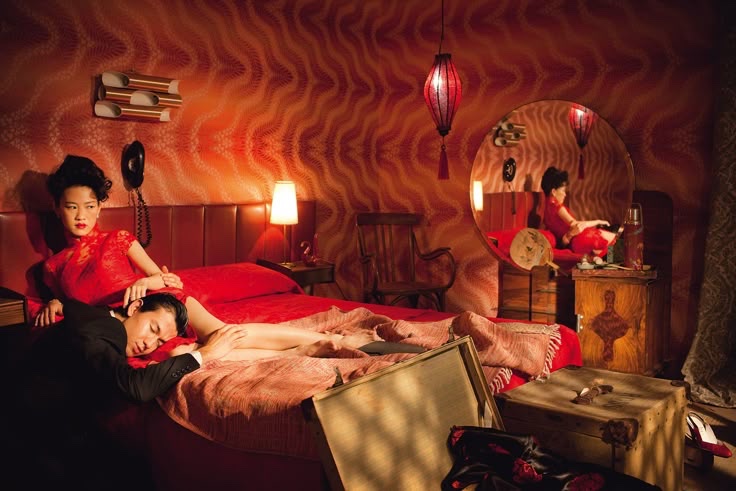

In the world of cinema, costumes serve more than just an aesthetic purpose – they are a second language, often running parallel to, and at times even surpassing, dialogue and action. A bright red dress against a gloomy backdrop can evoke a sense of rebellion, while an old sweater can carry the weight of a forgotten childhood.

Nowhere is this more evident than in visually meticulous films like Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017), where the fashion designer protagonist not only creates dresses but imbues each piece with subtle emotions. Each gown is a repressed feeling, sent without words. Similarly, in The Great Gatsby (Baz Luhrmann, 2013), the pearls, feathers, and fringed dresses become expressions of the opulence of the 1920s – also reflecting the gilded emptiness of the American Dream.

Each layer of clothing is also a layer of history. They capture the subtle shifts in society and the human psyche. In Little Women (Greta Gerwig, 2019), the transformation of Jo March’s wardrobe – from corsets to more masculine attire – is not merely an aesthetic choice; it symbolizes her quiet rebellion as a woman who wants to write, to live differently. The thread that stitches Jo’s dress is the very thread that connects the individual to the era – both personal and universal.

Not every character needs to vocalize what they feel. Fashion, in this case, becomes a wonderful companion. An outfit can be filled with contradictions – it can be a shield or a way for a character to scream out their loneliness.

The collaboration between filmmakers and costume designers is always a harmonious dance. One notable example is Jacqueline Durran, who won an Oscar for designing the iconic green dress in Atonement (2007), which is considered one of the most symbolic gowns in modern cinema. Another is Eiko Ishioka, who created the mystical fabrics in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), where fashion plays a role on par with acting and lighting.

Taylor | Cameron Truong