A teacher shares the strategy she developed to increase elementary students’ willingness to engage in productive struggle and meet their learning goals.

How to motivate students is an issue that teachers have always had to grapple with. Now, with the constant stimuli of internet-connected devices, it can seem impossible. By incorporating psychological, social, and cognitive theories from Fritz Heider, Bernard Weiner, and Alfred Bandura, respectively, into what I think of as a “Frankensteined” Cycle of Motivation, I have been able to break through the motivation barrier. Using this strategy, I focus on what students attribute their successes to, on setting up mastery experiences and opportunities for productive struggle, and on providing goal-related feedback.

Getting started

To begin with, you can have a conversation with students about productive struggle. I would do this during morning meeting, even in grades as young as kindergarten. Productive struggle is working through challenges to reach your goal, and in kindergarten we said that productive struggle is “trying your best and never giving up.”

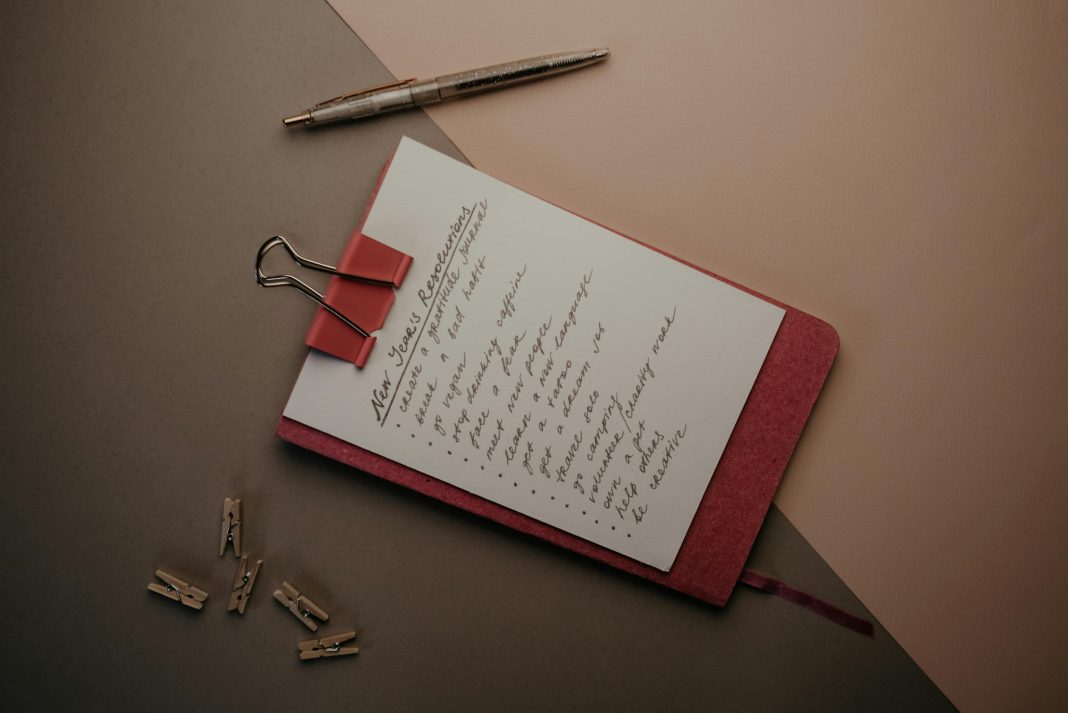

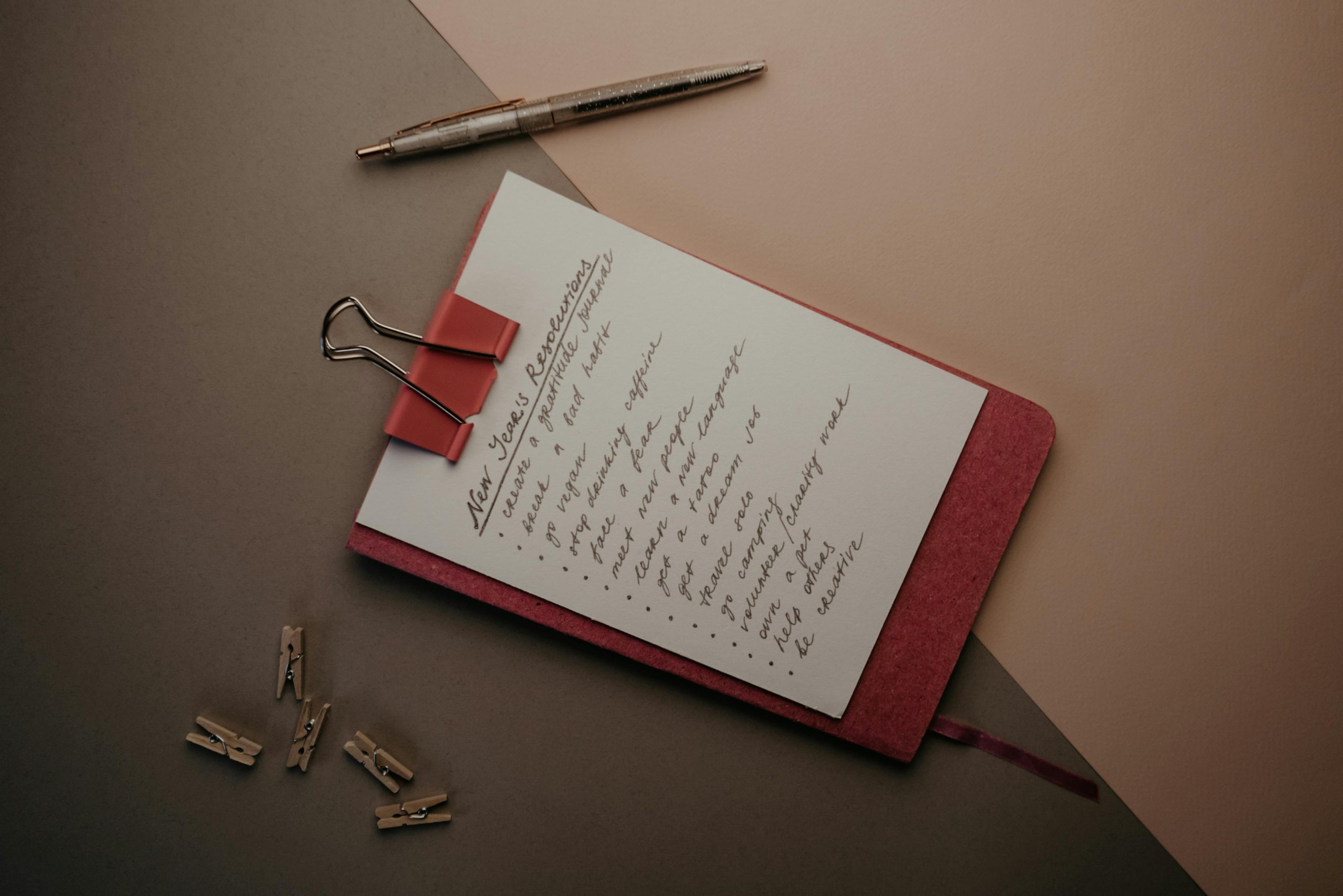

Creating an anchor chart for reference is important for continuing to reinforce the idea throughout the school year. The conversation on creating the chart is followed shortly by a conversation on attribution: When we succeed in our productive struggle, why? What do we attribute that success to? I have successfully had conversations about attribution and created an anchor chart in grades two through five.

The answers to the above questions should be limited to things that students can repeat and are a result of an action on their part. Being “smart” or “lucky,” for example, does not lead to success and isn’t repeatable because it isn’t in our control. Those descriptors are too vague. “Using my resources,” “asking for help,” and “studying or reading at night before bed” are all replicable actions that students can take to increase their subsequent chances of success.

A Classroom Culture of Motivation

During classwork and instruction, you can create opportunities for mastery experiences, purposeful opportunities that let students overcome a slightly difficult challenge so they can experience success and gain self-efficacy they’ll need for a more difficult challenge.

For example, when talking about comparing fractions in fourth grade, I start with ⅓ versus ⅔. While students are discussing the differences, ask how they know what they know. They might say they remember from third grade or they know about the number of parts or size of parts. Activate schema. They’re feeling confident and motivated to take risks. Ask if they’re ready for a challenge.

Challenges are nothing to be afraid of—they’re opportunities for growth—and I have never gotten a “no” at this point. Then challenge students with something like ⅓ and ⅙. This highlights common misconceptions. Ask them how they can use what they know to figure out what they don’t know. How can they use what they know about the number of parts and sizes of parts to figure out this question? Discuss. Ask questions and provide feedback.

When they have figured out a hard question, ask: How did we figure that out? What do we attribute our success to? Discuss the repeatable strategies they used, like using prior knowledge, reasoning, drawing a picture, discussing with a neighbor, etc. Then ask if they’re ready for another challenge. Their self-efficacy increases, which increases their internal motivation and their willingness to productively struggle.

For younger students, let’s say they are learning how to write letters. Start with o. It’s a circle (mastery experience). “Now, I wonder if you can write an a. Let’s try. It’s an o with a line.” Once they’ve done it, you’ll likely see increased motivation. “How did you know how to do that?” (Attribution). “Well, you just wrote an o and then a line because you knew how to write an o! I wonder if we could try a d, since you know how to write an o and a line.” And repeat. Throughout their learning during whole or small group, partner, or independent practice, remind them of what they have attributed their success to in the past.

Include Goal-Setting

This is also applicable to assessments. You can goal-set with students. Conferencing with students prior to the assessment to discuss goals and what actions they can take to reach their achievable and measurable goal prepares them for the post-assessment conversation and helps them to verbally explain how they’re taking ownership of their success. Then, after the assessment, conferencing with them to reflect on whether they met their goal and why or why not allows them to become self-aware about how their actions control their outcomes.

“If we didn’t meet our goal, what can we add or subtract from our actions to ensure our success? Do we need to adjust our goal?” This is not a time for shaming—it is only a time for reflection on actions and outcomes.

“If we did meet our goal, what actions do we take to refine and repeat to continue our success?” Students begin to understand that there are things they can control, but also, sometimes, even when they try their best, they still might not reach their goal, and that’s OK. “What can we tweak to help ourselves? Tweak the goal? Tweak the supports? Tweak ourselves in some way?”

When incorporating this Cycle of Motivation in my classroom, 93 percent of my students reached a new growth band. In Texas, we have Did Not Meet, Met, and Masters for the state assessment. I had students who traditionally scored in Did Not Meet or Met who moved up to Masters, and that included students served in special education, by dyslexia services, etc.

This had never happened before, and I was recognized by my district of 30,000 students for this accomplishment. I definitely attribute this to the above strategy of helping students take ownership of their learning by empowering them to make better choices based on what they can control, challenging them to overcome struggles, celebrating them, and helping them recognize how their choices affect outcomes. They were the most motivated, most powerful learners I’d ever taught.

This strategy is meant to help students become self-aware and motivated and to increase their self-efficacy through successful productive struggle. Another powerful by-product of this strategy, however, is a classroom full of students who love a challenge (and might challenge you on occasion) and who are able to internalize how they can control more than they think.

Cre: Edutopia