When World War II ended and the horrors of the Holocaust began to emerge, the focus was on the human cost, and seeking justice, retribution and answers for the survivors and bereaved families.

Then came the drive for reparations and restitution, which not only sought to compensate for the unimaginable suffering but also for the property seized by the Nazis.

And while many headlines have been made about valuable artworks – some worth millions – stolen from Jewish families, the story of millions of Jewish-owned books looted by Adolf Hitler’s forces is less familiar.

In their efforts to annihilate Jews and their culture, the Nazis stole books from European libraries, universities and other public and private collections across Europe.

While some were destroyed or sent to paper mills, many were saved for institutions the Nazis planned for so-called scholars to “scientifically” prove Jews’ inferiority. Though these institutions were never built, crates of looted books were sent to sorting centers to be processed – often by forced Jewish labor.

Diane Mizrachi, a librarian at UCLA, knew virtually nothing of the looted books until 2020, when she received an unexpected email.

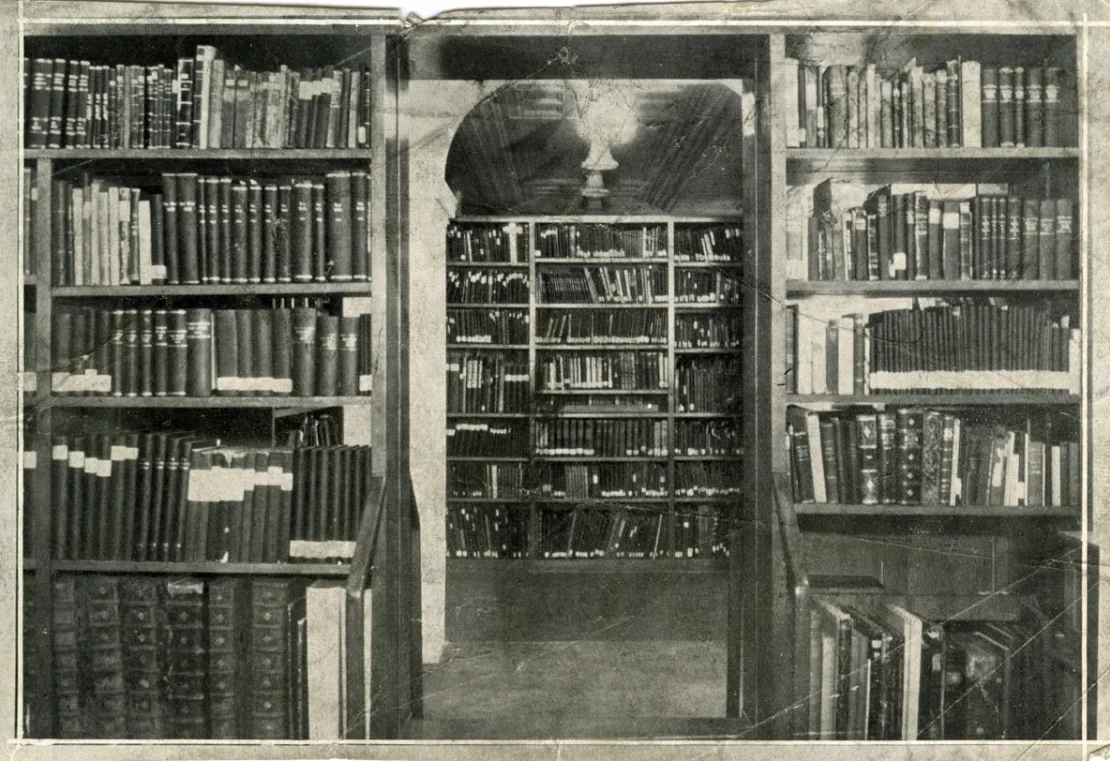

It came from a curator at the Jewish Museum in Prague (JMP) who has been trying to rebuild the collection of the Czech capital’s Jewish Religious Community Library (JRCLP), which was decimated by the Nazis.

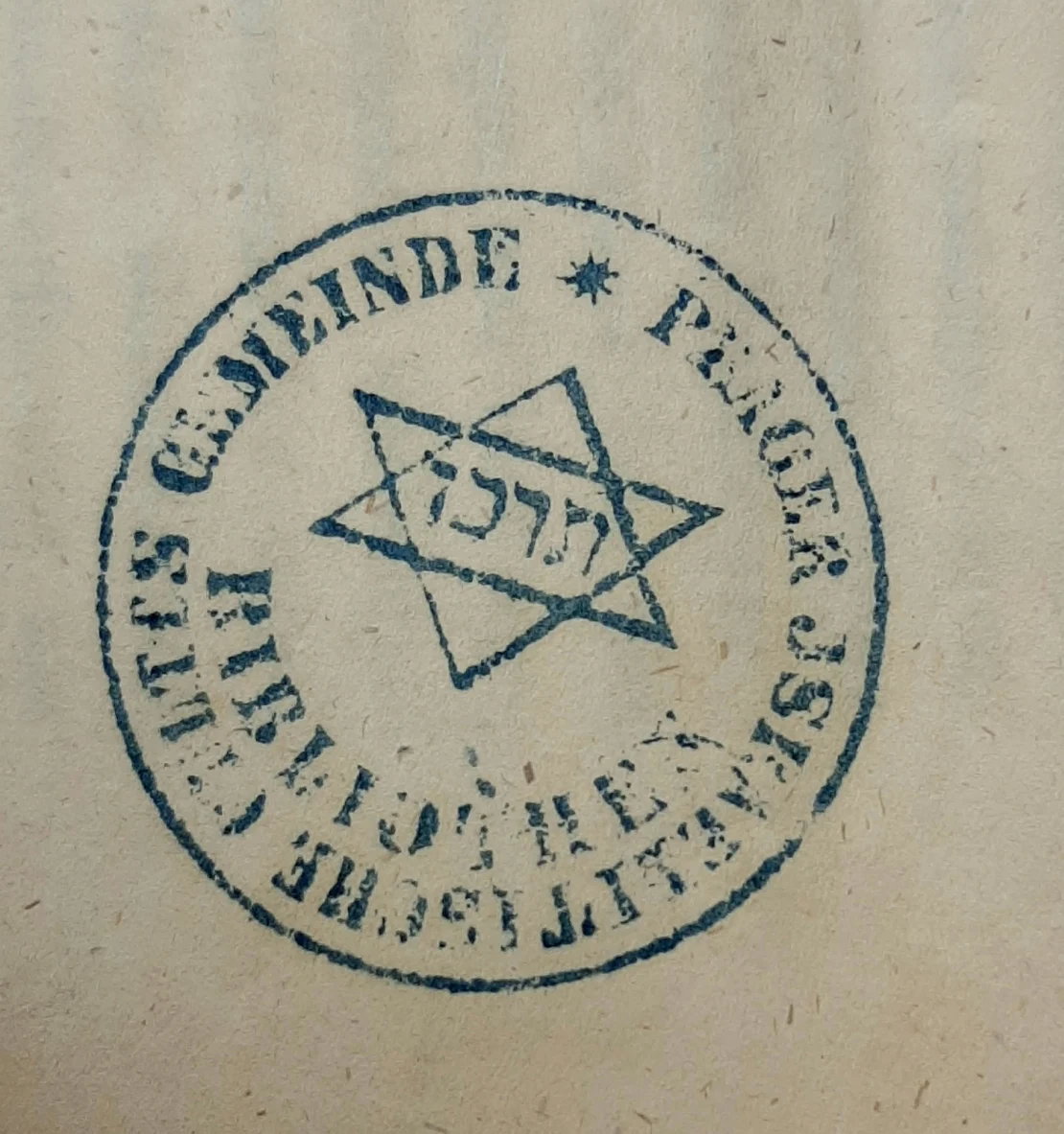

His painstaking search through an online repository of millions of digitized books led him to believe several books at UCLA had belonged to the library.

Mizrachi told CNN: “I got this email saying ‘I found that three books in your collection have markings of the pre-WWII Jewish religious community library and we would be interested in having them returned.’ I had no idea what to do with this so sent it up the chain of command.”

She soon learned that a similar request had been received from a German researcher several years previously and that UCLA had “quietly returned the book.”

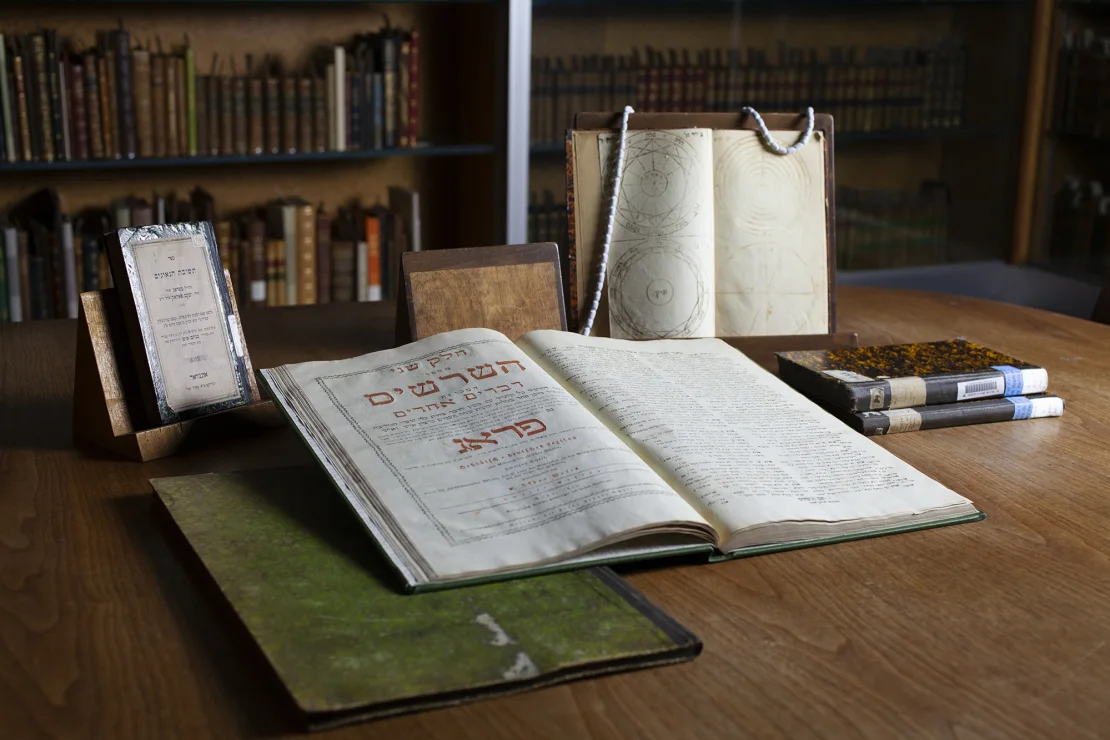

Mizrachi spent several months working with the museum to investigate the provenance of the three late-19th-century books in UCLA’s collection.

Eventually, six titles – among them religious texts and rabbinical commentaries – were repatriated in a ceremony in May 2022.

“At UCLA, we have dozens of such books, and I am certain that there are many more that have not yet been identified. I’m also working on collaborations with other librarians in North America, Europe and Israel who are dealing with their own looted Nazi-era books,” said Mizrachi.

“I see it as a moral and ethical issue,” she added. “Anytime that something has been stolen, whether it’s by imperialism or colonialism or oppressive forces, it’s a wrong. It’s a criminal act. The original owners might not be around or even their heirs to return them to, but their stories are important and that’s what we want to keep alive.”

After the war, what was left of the JRCLP was folded into the Jewish Museum in Prague, but with around 30,000 volumes and manuscripts looted by the Nazis, many thousands remain missing.

Michal Bušek, head of the museum’s library department, told CNN the internet, digitization of books, online auctions and the rise in provenance research has given the search greater momentum.

About 2,800 titles remain missing from Prague, he told CNN in an email. These books are not just lining the shelves of university libraries, but are also hidden away in museums, secondhand bookstores and private collections and listed in online auctions.

The process of recovering them is, therefore, not straightforward. The best-case scenario – as with UCLA – is that the museum works with the current owner to verify provenance and, ideally, arrange their return.

Bušek’s team has traced around 80 of the missing books so far and has had 63 returned. He told CNN the museum is currently in “negotiations” over the other volumes they’ve identified.

The search for Prague’s missing books began during World War II, when members of the city’s then Jewish community tried to track some of them down, Bušek said.

“We continue the efforts of our predecessors, who, in a situation where their own lives were threatened, sought to save the heritage and testimony of the Jewish presence in Bohemia and Moravia (Czech provinces occupied by the Nazis).

“This Library or the books is all that is left of them. Their legacy lives on. We want to bring the books back home where they belong.”

In neighboring Germany, meanwhile, organizers of a pioneering exhibition are hoping it will motivate “citizen scientists – school children, students, historians or anyone interested” to help trace another group of plundered books.

“The Library of Lost Books,” which is both online and running in physical form at the University Library Frankfurt until January 31, focuses on the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in Berlin (Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums), which was established in 1872 and dedicated to Jewish history, culture and rabbinical studies.

The institute was forcibly closed in 1942 under the Nazis, some of its estimated 60,000 books destroyed and others boxed up and dispatched across Europe. The new exhibition features some of the looted books.

Unlike Prague’s Jewish Museum, the “Library of Lost Books” is not seeking the return of the Hochschule books, but to create a database of their whereabouts.

“As there is no legal successor, this is now not a question of where these books belong,” said Irene Aue-Ben-David, director of the Leo Baeck Institute (LBI) in Jerusalem, which has created the exhibition with its sister organization in the United Kingdom and the Association of the Friends of the LBI in Berlin.

“For us it’s important that people are aware about the history of these books and report them and that we can document them online, but this isn’t about legal claims.”

The aim of the interactive project, say organizers, is to enable ordinary people to “contribute to elucidating a mystery that has thus far gone unsolved” while achieving “a sense of justice in the face of a Nazi atrocity.”

CNN