Red velvet suit, white fur trim, tall black boots, cozy (if not indulgent) pom-pom hat. Santa Claus’ uniform may have some variations, from Tim Allen’s off-duty outfits in “The Santa Clause” as he slowly transforms into the legendary gift-giver, to The Plastics’ spaghetti-strap-dress versions in “Mean Girls,” but his signature look is ingrained in pop culture and popular imagination older than anyone living today.

His dress codes ensure uniformity across mall Santas around the US, with aspects that are seemingly non-negotiable, despite the fact that he’s — spoiler alert — not real. A Santa Claus wearing a dark green suit at Bloomingdale’s for the department store’s “Wicked” partnership made tabloid headlines as the latest attempt to spark holiday outrage. One mom told the New York Post of the promotion: “Not everything needs to be changed or challenged… Green Santa is stupid. Hard pass.”

But Santa didn’t always wear red, and in fact, his outfits, appearance and height took nearly a century to become the iconic character we recognize today. His predecessors include the early Christian bishop St. Nicholas and his Dutch equivalent Sinterklaas; the hooded French patriarch Père Noël; and the German gift-bestowing baby Jesus, Christkindl (which, stateside, led to the mispronounced nickname Kris Kringle), among many others. But the Americanized Santa first began taking shape in the 1820s and kept evolving through poetry, editorial illustrations and advertisements.

Santa’s key features — a bearded, fur-wearing man pulled by reindeers on a sleigh — became canon thanks to the Clement Clarke Moore poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (also known as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”) in 1823, as well as a lesser-credited anonymous poem that preceded it in 1821 that named him “Santeclaus.” But everything else he wore was subject to interpretation.

“The 19th century was the time in which the arguments about what Santa looked like and what he wore were quite prominent,” said historian Gerry Bowler, author of “Santa Claus: A Biography,” in a phone interview. “It took about 80 years for American artists to settle on Santa’s outfit. Up to that time you could have put them in any color, in all kinds of robes and variations of it.”

Santa’s different looks

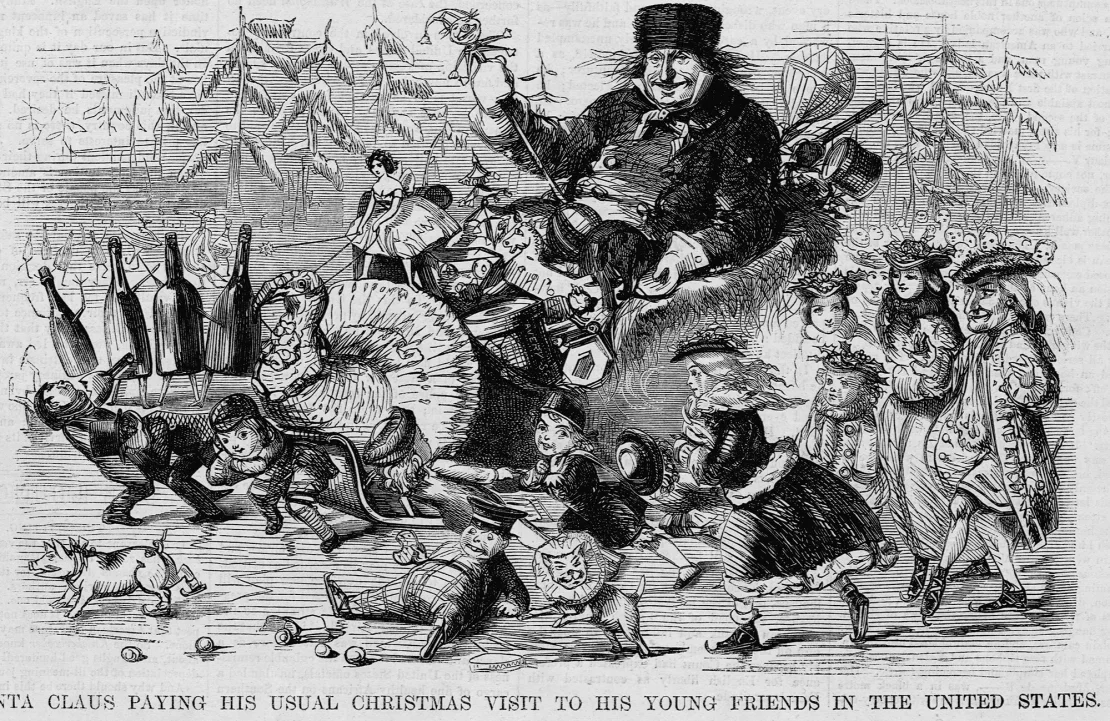

Some early interpretations of Moore’s vision show the jolly holiday intruder as a small and sly elfish peddler of goods who could more believably fit inside a chimney: An 1864 illustrated version of the poem dresses St. Nicholas, who traditionally wears Bishop garments, in a yellow suit and fur cap, as well as an oil painting in 1837, which shows him in a fur-lined red cape. But others played loose with his look: a P.T. Barnum advertisement from 1850 promoting the singer Jenny Lind shows him as a beardless Revolutionary War-era figure, while a 1902 cover for L. Frank Baum’s “The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus” puts him in a dark frock with animal print fur trim and flamboyant red boots.

Thomas Nast, the Harper’s Weekly cartoonist who gave us donkeys for Democrats and elephants for Republicans, played an instrumental role in envisioning Santa. He first drew him in 1863, during the Civil War, wearing stars and stripes as he handed out presents to Union Army soldiers. But the artist’s but most enduring image from 1881 is a version of him in a buckled red suit, nearly indistinguishable from today — though the political messaging to support military wages has been lost over time, according to the Smithsonian. He was followed by artists Norman Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker, who routinely drew a wholesome Santa in his now iconic suit for The Saturday Evening Post in the early 20th century.

“When you’ve got Santa in red and white fur trim on the cover of mass market magazines, it pretty much nails it down,” Bowler said.

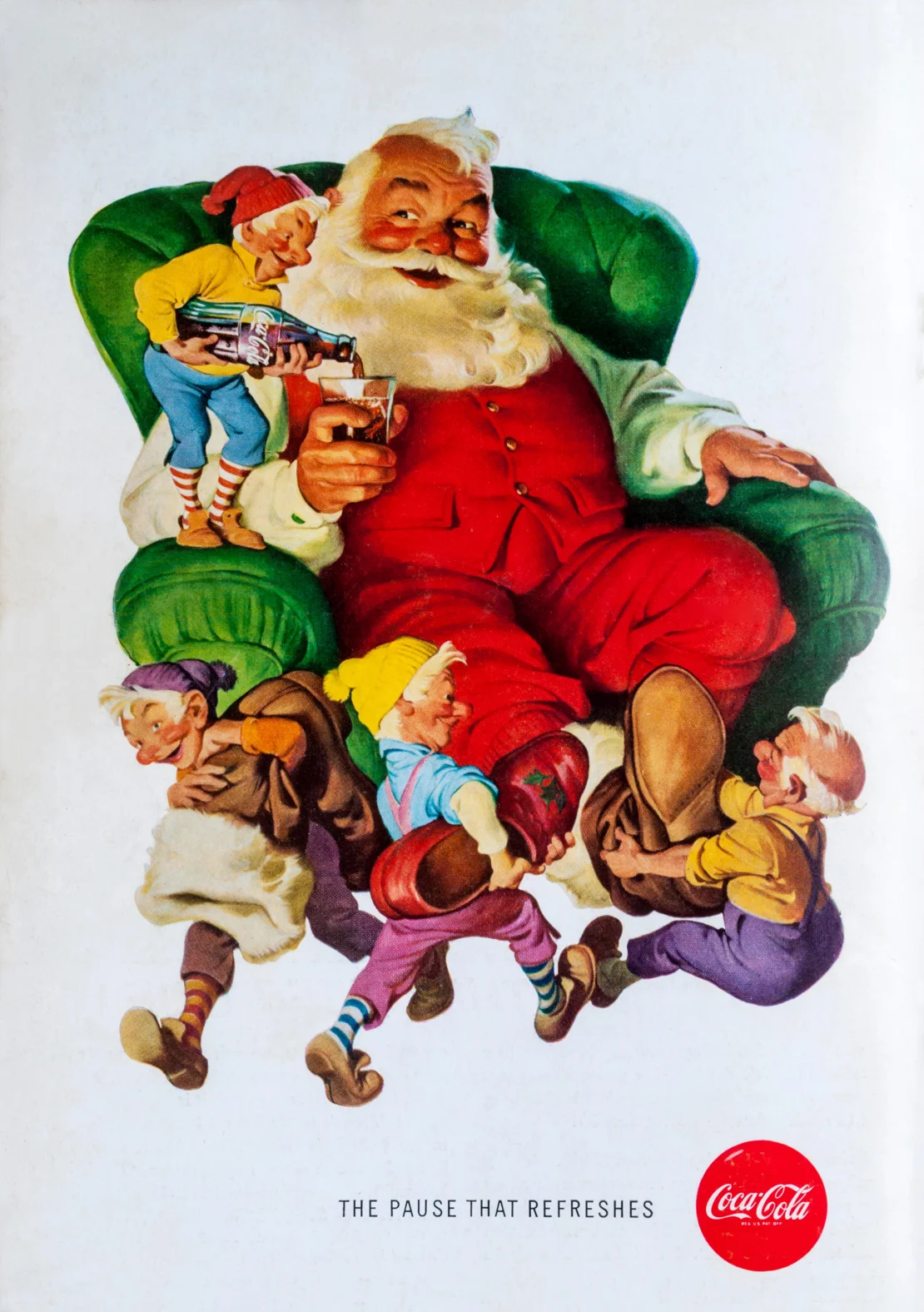

These artists’ formative drawings are often overshadowed by Coca-Cola’s long-running holiday campaigns, illustrated by Haddon Sundblom, which began in 1931 and have become synonymous with Santa’s look. Red-cheeked and Rubenesque, Sundblom’s version of Santa, originally based on a retired salesman who happened to be the illustrator’s friend, became wildly popular, and endures today.

“I think most people (believe) that Coke had something to do with the establishment of Santa’s red and white costume…you certainly see that all over the internet,” Bowler said. “But it’s not true. Santa’s iconic costume had been (determined) decades before.”

Coca-Cola wasn’t even the first soft drink to promote Santa in his suit, he added, with White Rock Beverages doing so during World War I, a few years before his first (pre-Sundblom) appearance for Coke.

“Certainly the (Coca-Cola) ads were ubiquitous — they were huge for years, so any variation on that gets people very upset,” he added.

A ploy for nostalgia

Santa’s earliest visionaries may not have picked out his red suit, but they did intend him to be a creature of nostalgia, according to the historian and author Stephen Nissenbaum. In his seminal 1988 book “The Battle for Christmas,” Nissenbaum charts the history of his character and challenged his oft-repeated origins as a natural import of the Netherlands’ St. Nicholas, Sinterklaas.

Instead, Nissenbaum points to a coterie of “antiquarian-minded New York gentleman” — to which Moore, the New York Historical Society founder John Pintard, and the writer Washington Irving belonged — who intentionally refashioned the Dutch figure in the 1820s as the symbol of a more family-friendly holiday amid rising poverty and crime.

In fact, according to Nissenbaum, the traditional precursor to Christmas in New England had been a drunk, rowdy and lascivious month-long celebration during the 17th and early 18th centuries, as a “safety valve” for the poor to “let off steam” in a more controlled manner than social unrest. One popular custom allowed people to enter the homes of the wealthy with the expectation that they would be given the best food and drink as a gesture of goodwill.

By Moore’s time, he explains, Christmas was not celebrated in any one unified way. Puritans had tried to quell it, while Evangelicals worked to convert it into a strictly pious occasion on December 25. Others still relished in the long tradition of mischief, leading to noisy, roving holiday street gangs.

“Not one of these ways of celebrating Christmas bore much resemblance to the holiday that most of us know today… In none of them would we have found the familiar intimate gathering or the giving of Christmas presents to expectant children. Nowhere would we have found Christmas trees; no reindeer, no Santa Claus,” Nissenbaum writes.

In this new version of Christmas, children — who, until around this time, were treated more like needy little adults — became the objects of generosity, absolving the well-to-do of the expectation to serve the poor. And Moore’s vision of St. Nicholas, who Nissenbaum argues was given a secular, working class makeover, neutralized the home invader into a visitor who makes no demands, but instead offers gifts.

As his clothes evolved, Santa Claus’ elfish nature faded, too, into a much taller, jolly, and purely benevolent guest.

“It’s a very unthreatening look, but it is alien,” Bowler noted of his outfit. “He is a creature of fantasy, of imagination, and he wears what nobody else wears. But over time, it becomes familiar.”

Bowler believes many of the features that won out over popular imagination were practical choices: Once it’s decided he’s from the Arctic, fur follows; red is vivid and contrasts against both his white beard and the white snow.

But tracing Santa’s exact style influences can get murky, since he has so many analogs in different parts of the world, some of whom have simply combined into this singular Westernized image. His hat alone has been credited to the ancient floppy Phrygian cap, felt pileus, and papal fur-trimmed camauro, among many others, but is now distinctly his own, and an irreplaceable part of his identity.

With such a varied fashion history, Santa’s closet used to be much bigger. Perhaps there’s room in the future to expand it once again — without the Christmas traditionalists melting down.

CNN