One of Narciso Rodriguez’s prized possessions is a pair of Victorian gloves, made painstakingly by hand. It’s a reminder that, as he says, “Good things last, and they’re meaningful.”

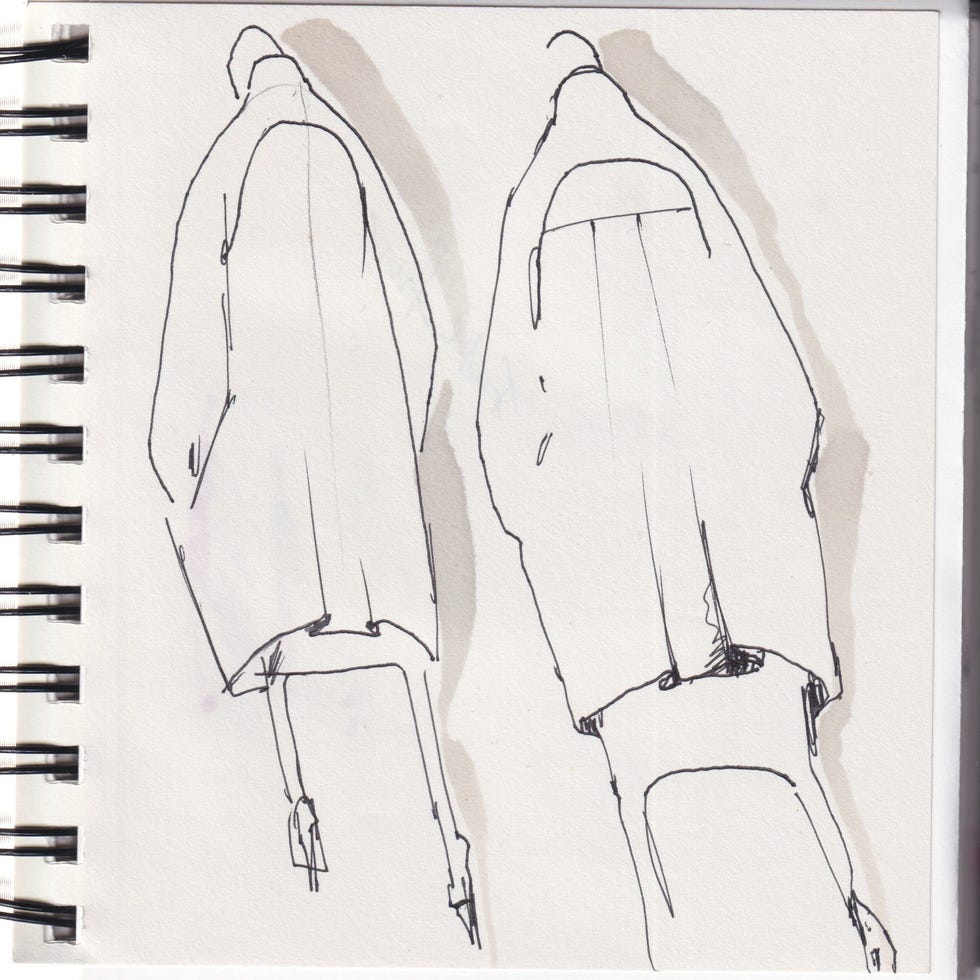

Creating those lasting, meaningful things is Rodriguez’s North Star right now. When he founded his namesake brand in 1997, he quickly became a boldface fashion name. At the outset of COVID, he shuttered his label, though he continued to design for private clients and run his thriving fragrance business with Shiseido. In the interim, he underwent what he calls “my personal reinvention,” redrawing the lines of his career. That meant carving out a smaller, more focused existence that allows him to stop work every day at 2:45 to pick up his 7-year-old twins from their school—conveniently located just around the corner from his studio. His kids can ride their scooters around his atelier while he arranges his fabric swatches or fits his custom designs. He now has the freedom to “create a collection that’s not on a deadline, and on my terms, and forge a new way forward,” he says. “I just don’t want to be trapped in a machine. I want to get back to the things that bring me joy: my craft, the materials. And it’s been a great experience, because I’ve had the luxury of time to perfect this concept.”

Upon his return, Rodriguez says, “I didn’t want to fall into the same trap of department stores and deadlines and shows.” He has received “interesting proposals,” he admits, “but I couldn’t imagine being on a plane, putting on shows in Europe, and missing out on one day of my kids’ life.”

Decades ago, Rodriguez was a part of the go-go revolution in American sportswear that brought New York designers to the fashion forefront. While he was still at Parsons, Oscar de la Renta took him on as a mentee. “He loved that I was this young Latin man trying to get ahead,” he says. Now he’s paid it forward, serving as a beacon to designers like Willy Chavarria, who has said, “There would be no Willy Chavarria without Narciso Rodriguez.” (The designer is touched: “Gosh, that was a lovely thing for him to say. It’s so hard for me to wrap my head around it.”)

Rodriguez went on to work for two titans: Donna Karan (at Anne Klein) and Calvin Klein. “When you’re in it, you don’t realize what’s going on, which is true for anything in life. And when you look back, you go, ‘Wow, those were such crazy times; we worked so hard,’ ” he says. His Calvin colleague Carolyn Bessette became a muse of his; the minimalist bias-cut dress he designed for her wedding to John F. Kennedy Jr. remains probably his best-known work.

Bessette Kennedy’s wardrobe continues to fascinate us long after her untimely death, and Rodriguez is unsurprised. “Her style was never a production,” he says. “It was just something innate. Even when she wore the most complicated Yohji piece, it was natural….So often you see people on a red carpet and you wonder, ‘Who convinced them of that? How uncomfortable do they look?’ It doesn’t fit their personality.” In his time in the industry, he’s seen fashion shape-shift into the corporate juggernaut it is today. “I know it’s a business, and everyone’s getting paid and courted and gifted and flown, and the stylists are now celebrities, and they’re getting flown in and paid off. It’s the antithesis of what good style is,” he says.

Rodriguez went on to be closely associated with other women whom he has dressed, now, for decades, like Julianna Margulies and Claire Danes. He first met Danes when she was only 16, and he has designed wedding gowns for both actresses. These kinds of relationships are increasingly unusual in fashion, where celebrities are often outfitted for a one-off event or as part of a contract. Rodriguez is more like an old-school couturier in that way, following his muses throughout the stages of their lives.

Growing up in a Cuban American family in New Jersey, he was surrounded by women who shaped his view of what style could be. “They were bold; they loved fashion, fragrance, the art of dressing up. And it made a big impression on me at a young age.” One relative, Nana Concha, was “a real Auntie Mame kind of character,” he remembers. “As all these Cuban newlyweds immigrated to the United States, she was the magnet. She set them up, gave them a place to sleep; she taught them how to cook, how to get by. She was a real force in the lives of so many people, a very loved woman.” He was “completely besotted with her, and her beehive, and her makeup. She made herself Chanel-looking suits, and wore fantastic stilettos with pointy toes. It was a life lesson: It doesn’t take great wealth to have great style.”

For Rodriguez, the true test of his work now is its ability to last for generations. A client of his stored her Narciso treasures for 20 years to give to her daughter. “I thought, ‘God, that’s the greatest compliment.’ It feels like a win that the passion that went into each one of those dresses is recognized and appreciated—and then kept for the next generation.”