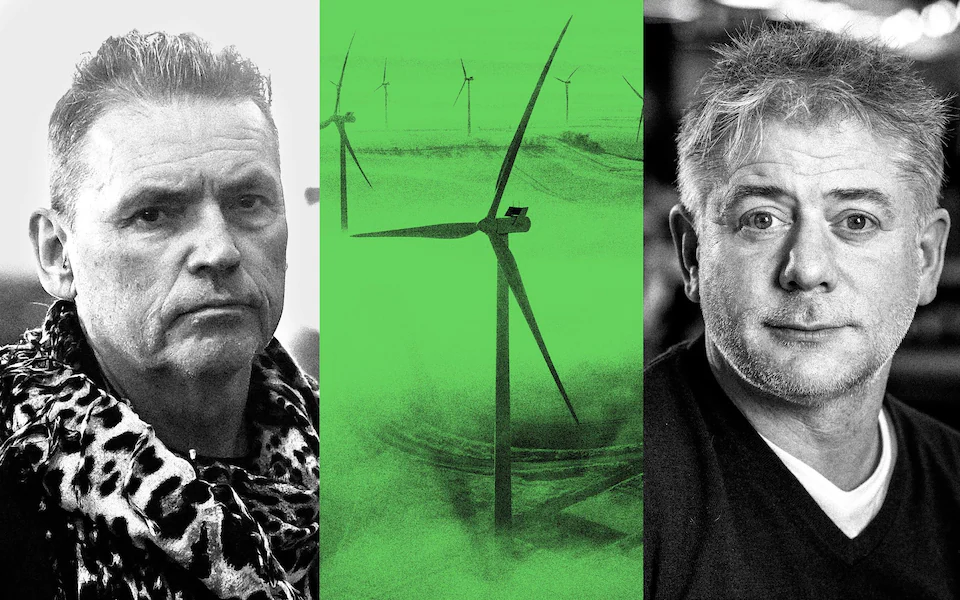

Britain’s green energy tycoons are at war.

Greg Jackson, the chief executive of Octopus Energy, is taking on Dale Vince, Ecotricity founder, in a fight over the best way to achieve net zero.

At the heart of the battle is a radical new scheme being considered by Ed Miliband, the Energy Secretary, called zonal pricing, under which Britain would be divided into zones with different power prices.

In a round of briefings last week, Jackson set out why Octopus, the UK’s biggest energy supplier, is backing the idea – prompting a swift backlash from Vince, who ridiculed the scheme as unworkable and questioned his rival’s motives.

Jackson’s key criticism of the UK’s current “crazy” power system is the way it has encouraged developers to build vast wind farms in Scotland, despite there not being power cables to transfer the electricity generated to customers.

This leads to thousands of turbines being unnecessarily turned off, he says, costing billpayers millions of pounds in the process.

“If you look at what’s causing our record high energy costs at the moment, we banged a load of renewables on to a system that wasn’t designed for it,” says Jackson. “As a result, the biggest wind farms in the UK, that should be the most productive, stand idle the vast majority of the time.”

Jackson calculates that zonal pricing would save households at least £3.7bn a year, equating to around £132 per customer. That figure will certainly appeal to Miliband, who this summer will decide if zonal pricing is introduced.

However, the scheme is not without its critics.

Just hours after Jackson’s briefing last week, Vince released a carefully crafted report warning that zonal pricing would be massively complex, delay the UK’s net zero programme and burden poorer households with extra charges.

And that was before he launched a personal attack on Jackson.

“I don’t understand why Greg Jackson is evangelical about it,” says Vince. “But part of me thinks that he’s looking for a cause to campaign for and make a name for himself because there are so many better things we can do to bring energy prices down.”

Lower costs, or more uncertainty?

The spat marks a new phase in the war over zonal pricing, one that has been simmering for at least a decade but was previously confined to academics, energy analysts and suppliers.

It first came to the fore last year when Miliband ordered a review of electricity markets. But the debate has been revived of late after zonal pricing became a real possibility.

But what is zonal pricing? And why do Vince and Jackson care so much?

At the moment, electricity costs are the same across the UK. However, under the proposed new regime, the country would be split into 12 zones – with power prices determined by geographical supply and demand.

Prices would fall for consumers close to energy hubs such as wind farms, but would rise if electricity had to be imported from other zones.

The practical result, say most experts, would be to cut power prices in the North – where there are lots of wind farms – and sharply increase them in the South.

Jackson loves the idea because he believes it would stop renewables developers from putting wind farms in places starved of infrastructure and households.

“It would be mad to keep building on our current system because you’re building wind farms that are idle more often than they’re productive,” he says.

“The more of them you build, the worse that gets. If you introduce a more sensible market, meaning zonal, then all that infrastructure should be more productive, and costs come down.”

Vince, however, disagrees: “Zonal pricing would be one of the most complicated reforms that we could make to our energy system.

“It would be lengthy and difficult to implement, with it being unlikely that it would be finished before 2030, more likely much later, which would create a huge deal of uncertainty for investors and market participants.”

The row over zonal pricing comes at a turbulent time for Britain’s energy system, with Miliband already pledging to remove gas-fired power stations from the system by 2030 – a hugely ambitious target.

Other forces are at work too. The long-term collapse of British industry saw demand for electricity plummet to 317 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2023, its lowest since the 1980s.

But, according to Milliband, the shift to heat pumps and electric vehicles will reverse that decline. By 2050, UK demand could reach 700TWh – more than double current levels.

Meeting that demand will mean more than tripling the UK’s generating capacity from its current 116 gigawatts (GW) to more than 400GW.

That increase equates to nearly 100 nuclear power stations the size of Hinkley Point C, currently under construction in Somerset.

Some experts have warned the reorganisation needed for zonal pricing would delay decarbonisation and disrupt the expansion of the grid.

Jackson, however, believes it would actually help by forcing developers to build wind and solar closer to places where demand is highest. For example, closer to England’s power-hungry cities rather than in Scotland.

Such arguments may make economic sense but they are not without political risk, particularly if it means carpeting the English countryside with renewables.

Despite this, Jackson is adamant that the pros outweigh the cons, rejecting Vince’s view that zonal pricing is an unnecessary distraction.

An Octopus spokesman accused Ecotricity of parading the “familiar rhetoric of other incumbents with vested interests in maintaining the status quo”.

“But even they can’t argue against the hard truth,” they added. “The UK has some of the highest electricity prices in the world, with severe impacts on people and businesses. Our current electricity market design is failing consumers and is no longer fit for purpose. “

Industry-wide debate

Jackson’s view has some powerful backers, including Ofgem, the energy regulator.

In January Jonathan Brearley, Ofgem chief executive, told MPs: “This is not a unanimous issue, but we are, broadly, very supportive of moving to a system that has zonal pricing. We think it improves efficiency. There are ways in which you can deal with some of the regional inequalities that might result.”

Neso, the National Energy System Operator, whose job it is to run Britain’s electricity networks, is also keen. “We are in favour of zonal pricing,” said a spokesman.

However, there is far less agreement across the rest of the industry.

Energy UK, the trade body for power suppliers, counts Octopus as a member yet has come down against zonal pricing. Renewable developers also largely back Vince.

In a joint statement, Solar Energy UK, which represents solar developers, and Renewable UK, the wind industry trade body, said: “We remain sceptical about the claimed benefits of a zonal system.”

Others argue that the battle over charging policies has forgotten one key group: billpayers.

Jackson suggests the savings will lie in the infrastructure: invisible to consumers but offering suppliers big rewards.

“The major benefit of zonal pricing is not that we expect households in different regions to behave differently,” he says. “It’s things like the interconnectors, the huge grid-scale batteries, the stuff at the backend, it will all behave very differently, saving everyone a fortune.”

However, for Ecotricity – a much smaller company without the sophisticated technology underpinning Octopus – zonal pricing is not worth the hassle.

“Zonal pricing would be an incredibly complex trading arrangement, increasing our costs for sure, along with risk and uncertainty,” says Vince.

“I’m just surprised Greg’s chosen this incredibly complex thing to lobby for that’s so fraught with uncertainty.”