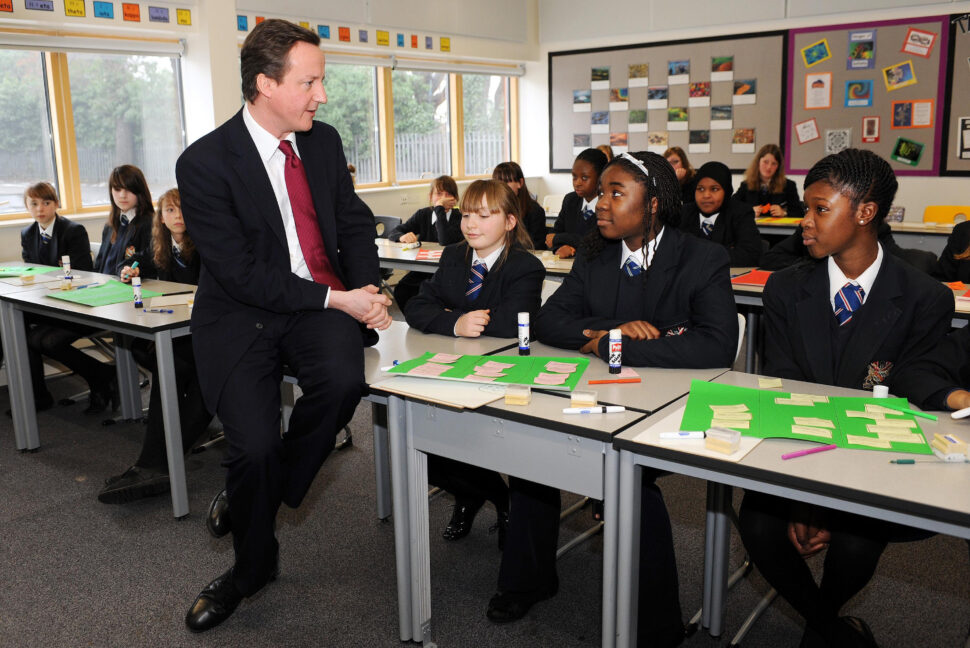

Last week, in language reminiscent of David Cameron a decade and a half ago, Keir Starmer expressed his disdain for a “watchdog state, completely out of whack with the priorities of the British people”. Their words may differ, but the language hasn’t changed.

In 2010, the “bonfire of the quangos” torched several agencies committed to support and development (including the Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency, the National College and the General Teaching Council) while empowering those concerned with compliance and regulation, notably Ofsted and Ofqual.

Our system’s low-trust focus on regulation is accentuated by a language of school improvement that has long been rooted in deficit-thinking. It is articulated in a discourse of control, compliance, monitoring and inspection, rather than of creativity, innovation, development and quality assurance.

There was some justification for this when the school improvement movement emerged in the 1980s. It is beyond question that performance metrics, inspection and appraisals drove up outcomes for many young people.

But forty years on, our education system is in a wholly different and better place. Rapid improvement (most evident under New Labour when need was matched by investment) has long since plateaued.

Indeed, the strategies that once drove up standards are now driving out teachers and leaders, negatively affecting the wellbeing of children and staff – sometimes with tragic consequences – and creating, in Ofsted’s own phrasing, a cadre of “stuck schools”.

It’s only the experience of the pandemic that has caused policymakers to begin to acknowledge, almost begrudgingly, that school improvement is harder in some settings than others and that socio-economic background and local context have a profound impact on outcomes. This is a reality that the success of a smattering of media-savvy ‘super heads’ cannot fix.

Lockdown didn’t create the multiple layers of educational disadvantage it exposed, but it undoubtedly accentuated them. It also crystalised the question of whether conventional schooling can meet the needs of all young people; if not, what can?

DIFFERENT FRAMES ENGENDER DIFFERENT RESPONSES

The existing language of school improvement frames current levels of pupil absenteeism as a crisis of school attendance; a new language would frame it as an issue of educational engagement. Different frames engender different responses.

It also measures success against criteria built for a stable world that has long disappeared in the rearview mirror. Thus, Martyn Oliver’s Ofsted consultation asks how we should inspect, not whether this is the best or sole means of quality assurance, which is surely the objective.

The same goes for league tables and performance management systems: quality assurance methods have become unchallengeable ends in themselves.

Sadly, this week’s interim report from the curriculum and assessment review reveals the same thinking: our current approach, it argues, only needs tweaking.

A common refrain across these reforms – in education and across government – is a commitment to ‘evolution, not revolution’. No doubt intended to reassure, this risks ignoring the scale of the challenges and opportunities ahead: AI, assessment, online learning and SEND.

No one would argue for a political pendulum swing, but framing reform in this way is itself part of this language of low trust and deficit.

The sector is crying out for a longer-term vision underpinned by a new language for school improvement, one defined by twenty-first century purpose, not twentieth-century metrics.

We need to reward schools for ingenuity, innovation and creativity, not the ability to remain ‘faithful’ to a particular reading scheme or the implementation of politically fashionable policies and practices.

In this context, the test of Bridget Phillipson’s new RISE teams will be whether they can dispense with the language of ‘monitoring’ and adopt one that is about collaboration.

Encouragingly, this appears to be the policy’s intention. Time will tell whether the pressures of political accountability once again trump the need for smarter school support. But at least the language from the DfE is right.

Sir Keir’s is too; we do need to roll back the watchdog state. Phillipson, Francis and Oliver have been given the opportunity to lead the way. Some will find it easier to embrace a new language of improvement than others, but all will have to – or we will find evolution is quickly outpaced by events.