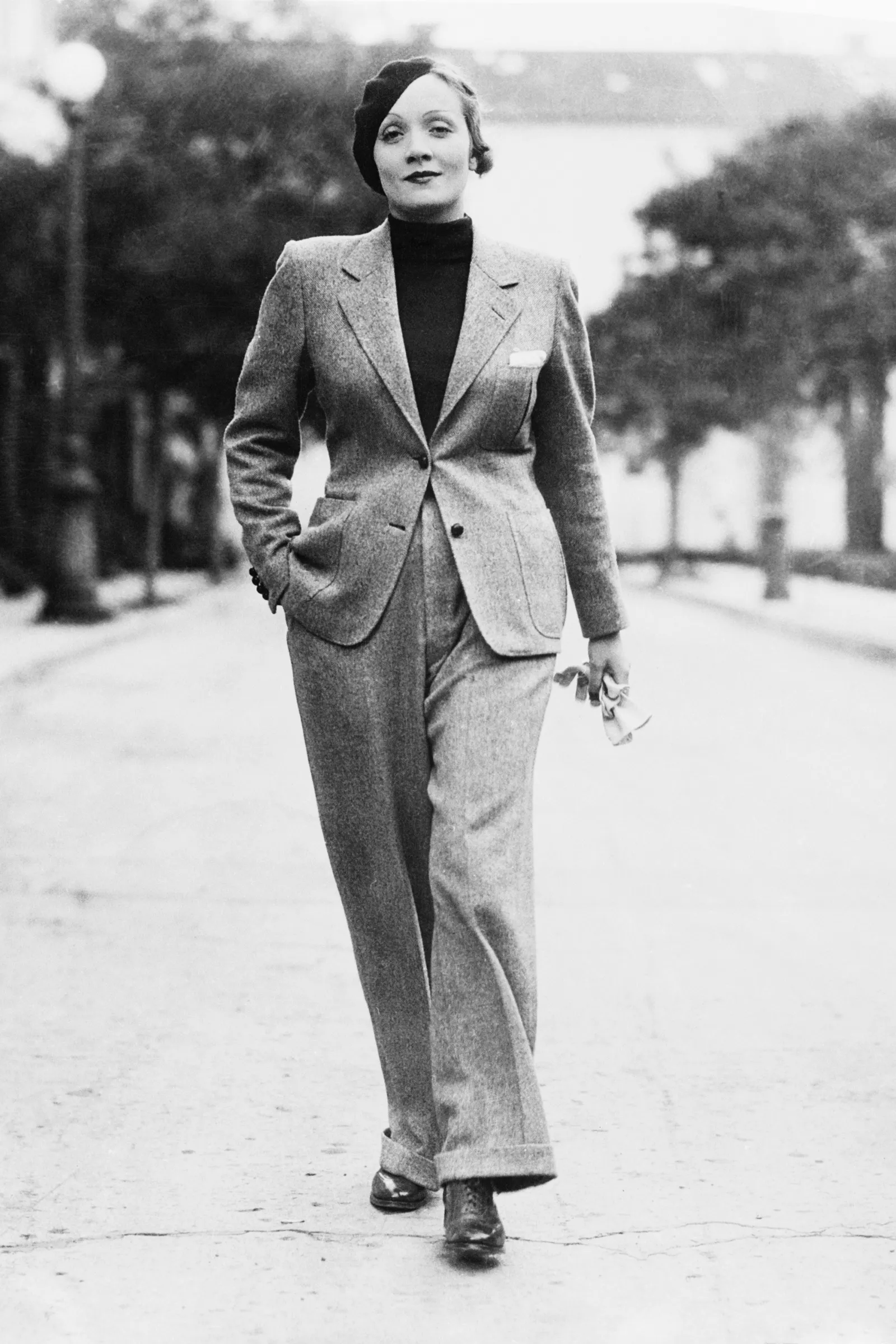

For my high school graduation present, I asked for my first suit. At the time, suits, I believed, were the chicest thing a woman could wear. (This is the kind of insane thought that, once embedded in the mind of a teenage girl, is impossible to trace or dislodge.) To me, suiting represented a bordering on French sophistication unreachable for a high schooler who had never been to France, a sexual confidence without crassness, a maturity without stodginess. The suit conjured cigarettes and witticisms. Now that I was to begin my voyage into womanhood, I wanted to look like Marlene Dietrich or Katharine Hepburn or Diane Keaton or Julia Roberts, all perk and pout. Once I had a suit, I felt sure, I would join the ranks of real intellectual lookers. My father, for whom the word casual holds no meaning and a great lover of suiting, carted me down to the West Village, where we went to several vintage stores and I had my dreams strangled by roughly 3.5 meters of pinstripe fabric.

The boyish ’fits I tried on just didn’t look right. I looked like a female news anchor. I looked like the curvaceous vice principal of my public middle school; like an elected official buckling under public scrutiny, the cracks in her campaign accentuated by off-the-rack slacks; a buxom background goon in an R-rated version of The Godfather. Pulling at the already taut material, I fixed an evil gaze at my chest. I realized that the thing standing in the way of my vision was actually two things. Yes, I lived it: I was a 17-year-old with a massive rack.

I’d barely even had time to participate in the honorable teenage tradition of envying other girl’s chests when my own sprung forth, arriving to the party early and severely overstaying their welcome. They gummed up my dresses, drew unwanted attention, and became home for things I’d thought I’d lost: crumbs, anxieties, misplaced hopes. Having breasts was one thing, but dressing for them, in my eyes, meant a world of lumpy sweaters and blouses that ballooned out slobbishly. Was my vision of washboard androgyny unattainable? Was my body just ill-suited?

Nonetheless, I took home a massive navy pinstripe Etro suit. My dad adjusted it on my shoulders, issuing a threat: “You’ll own this forever.” I debuted my new suit at a family friend’s wedding, where someone, no fault to them, confused me for a cater waiter. I failed to remember the moment in Annie Hall when someone asked Diane Keaton if there were any more pigs in a blanket. There weren’t, by the way.

Yet I couldn’t let go of the suit. I came back to it again and again, and as the years passed, my approach to style and my body changed. In college, I wore it open with just a lacy bra underneath. I wore it with a stupid American Apparel schoolgirl skirt. I wore it with a bowler hat. At some point, I retired the pants entirely. Part of what I was longing for, I realized, was a lifestyle (cigarettes and red wine, people taking your opinions seriously), and it’s almost impossible to feel sophisticated and sexy when you’re 17 because you aren’t (but you should try anyway) and nobody takes you seriously.

Eventually, I let go of the girl in the suit—that wan, haunted woman—to embrace the suit. After all, these were my clothes for me, not for Jane Birkin! So I started to buy more. For the most amount of money I’d ever spent at the time on a single item of clothing (a whopping $350), I bought a vintage Jean Paul Gaultier set with a high waist and a matching belt from the Chelsea Flea Market. From a charity shop in Rhode Island, I got a navy linen suit with a standing collar. I acquired a brown tweed Norma Kamali suit with a slick velvet trim.

I’m happy to report that suiting is back in a big way (hello, Saint Laurent!), and now, sporting a collection of suits (God, is there anything nerdier than a collection?), I’m here to give my tips: the busty girl’s guide to not busting out. Do not try to be subtle. Do not try to be French. (The things American women have done in the name of French style are some of the worst decisions in our sartorial history.) Angles, people, angles! I want a tiny cinched waist or a big ol’ shoulder pad. I want a bow tie, massive hair, and drama! Go to the tailor, and go to the haberdasher (but do not buy anything—that bowler hat is not your friend). Belts are good; suspenders are terrible. Oversized is great; if you’re going oversized, go big or go home. A suit is an excellent investment because you don’t have to wear both parts together. Have fun. Wear the pants with a humble cardigan and ballet flats and then the jacket with shorts and boots another night. Finally, if Kim Kardashian can do it (on the cover of GQ, no less), you can too.

When done well, suiting is powerful. When done poorly, it’s still, unfortunately, powerful. Suiting is the rare conduit between how you want to be seen and how you are seen. It is a uniform, and like all uniforms, it has a specific purpose: to make the wearer sexy and strong. My father, of course, was right. I still own the Etro suit, and I break it out at least once a month, which is about as much airtime as you can get in my closet. I’ll own it forever.